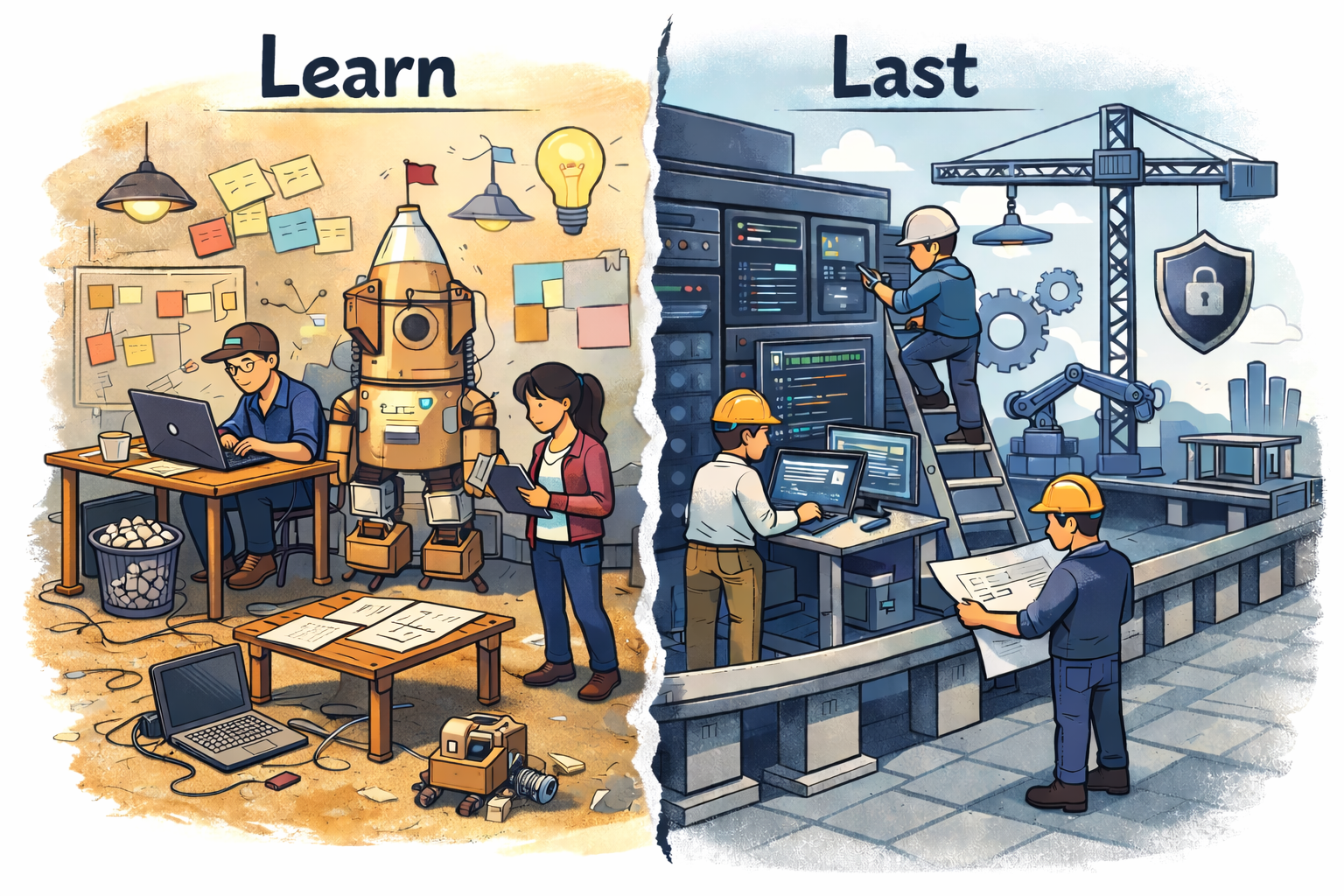

Building to last vs Building to learn!

Intent first: learn vs last

Software product teams build two very different kinds of work: artifacts to learn and systems to run. Confusing the two is one of the fastest ways to burn time, create friction with engineering, and ship the wrong product, late. This post proposes a simple lens: match your quality bar and process to intent, learning or longevity, to reduce waste, shorten time-to-value, and ship more reliable systems.

What building to last looks like

- Goal: reliability, maintainability, evolvability.

- Done means: observable in production, documented, tested, operable.

- Quality bar: strong architecture, automated tests, monitoring, clear ownership.

- Optimizing for: future change cost, incident reduction, team velocity over time.

What building to learn looks like

- Goal: reducing the risks of investing in the wrong thing.

- Done means: we reduced the key assumptions enough to make a decision (proceed, pivot, or stop).

- Quality bar: credible enough to get the message across; honest enough not to mislead.

- Optimizing for: cost of learning (lower is better), speed of learning, strength of evidence.

Why teams default to building to last

Many organizations historically separated “deciding” from “building.” The research process and solution design were done beforehand, specifications were sent over and engineering was accountable for delivery and long-term maintenance. In this context, engineers naturally focus on building high quality code, with good test coverage and an architecture that is geared towards lasting.

Changes with the rise of Product management and design practices

Modern product teams embrace the fact that building software is full of uncertainty.

- Does the problem exist in a meaningful way?

- Does anyone desire a solution for that problem?

- Would they pay for a solution, or change behavior to adopt it?

- Would they adopt it and know how to use it?

- Can we even build a solution in a reasonable time? How much effort and costs would running the solution take? The cross-functional team (PM, design, engineering) runs discovery to replace assumptions with evidence. Rapid prototyping plays an important role in their toolbox, to reduce the risks of product (customer value, technical feasibility, usability and business viability), before committing more resources.

When does one switch from learning to lasting

The switch isn’t a single moment but rather a decision. In practice, many parameters will come into play, among which:

- Value risk: Credible user evidence that the problem is real and the direction works.

- Business viability risk: Solving this problem will improve the company business, aligning with the current strategy with a good return on investment compared to what we are about to invest.

- Feasibility risk: We know the solution is doable in a reasonable timeframe. An early prototype existing is best to ensure that.

- Usability risk: We have evidence of how the solution should feel like as an end user. A UX prototype, that has seen few customers and didn’t ring alarm bells, works best.

- Timing: it is the right moment to invest compared to other initiatives and constraints. The product trio (PM, design, tech) is typically the best forum to make this call, with stakeholder input when trade-offs impact strategy or investment.

Changes in build to learn in the age of AI

AI has changed discovery profoundly: prototypes that used to take weeks can now be produced in hours. Tools for rapid UI generation (Lovable for example) and coding copilots (GitHub Copilot for example) dramatically lower the cost of exploring multiple solution angles. These tools have another advantage: Their simplicity empowers the product manager and product designer to use AI tools and build new prototypes of features themselves, increasing further the capacity of the team to solve customer problems. AI brings new risk though: The prototypes become too convincing, and stakeholders start treating them as production-ready. Practical guardrails help: label prototypes explicitly, avoid connecting them to production data, and treat any path to production as a deliberate rebuild with production quality gates.

Changes in build to last in the age of AI

AI can speed up implementation and help support the engineers’ work, but it does not replace the need for engineering judgment. When building to last, quality gates remain non-negotiable: architecture coherence, automated tests, security considerations, observability and, documentation. And these quality gates take time to do properly.

Building for both with intent

Most delivery pain I have seen comes from a mismatch between intent and expectations: treating learning artifacts like production systems, or treating production systems like experiments. If you want one practical habit to take away, it is this: state the intent before starting the work, then align the definition of done, quality bar, and stakeholders expectations accordingly.